In order for the Quality Jobs Fund (QJF) to make a considerable impact in the long-term, sustainable development of low-income communities, it’s important we look towards the rapidly evolving future of the American labor force.

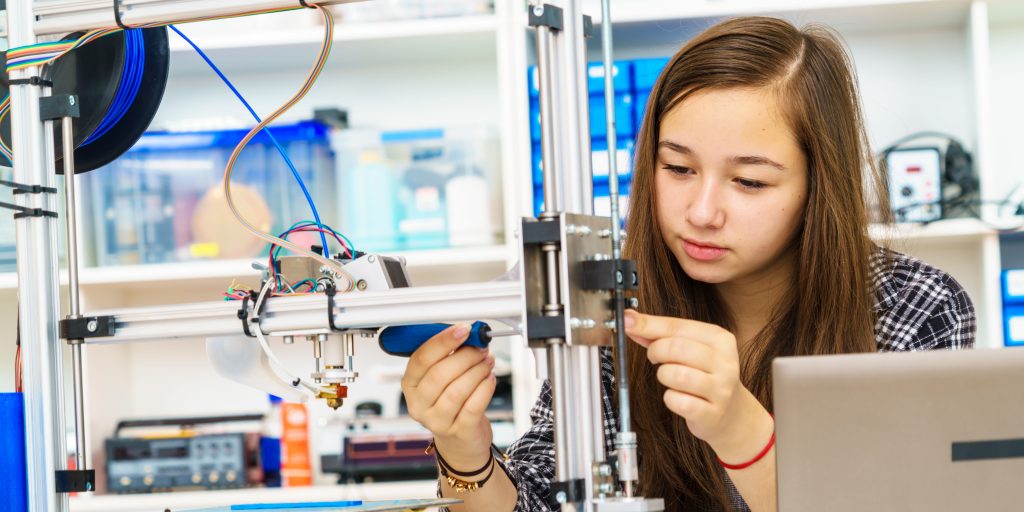

Investing in intermediaries that will support the growth of small businesses anticipating technological advancement, and that equip low-income workers with the skills necessary to fulfill high-quality jobs in developing fields is key to the Quality Jobs Fund strategy, along with defining a quality job within these shifting dynamics.

Here are a handful of research-driven ideas, innovative solutions, and tested models we’re learning from to generate key questions about the #futureofwork.

1. Who is the new working class?

The demographics of the United States’ working class is rapidly changing in its racial, ethnic, age, and gender representation, because the country’s demographics in general are shifting.

Black and Hispanic workers have long been an unacknowledged part of the American workforce, and the influx of immigrants over the past 50 years has added to its diversity.

A number of interrelated social, cultural, and political shifts since the 1960s have resulted in a dramatic change in family dynamics and a convergence of gender roles. This has led to a steady rise in women’s participation in the labor force, with an increasing population of working mothers serving as their families main breadwinners.

What types of jobs employ the new working class? Mostly service work — and they’re widely underpaid.

Young adults born after 1980 (Millennials) have now surpassed Baby Boomers as the largest, most educated, and diverse U.S. generation, many of them struggling financially with student debt and still living at home. Though the cultural and technological gap between these two generations is wide, as the population of seniors rapidly grows across the world, and the retirement age gradually rises in the United States, both are struggling with job insecurity, with seniors perhaps most vulnerable to long-term unemployment.

What types of jobs employ the new working class? Mostly service work: janitors, customer service reps, delivery drivers, home health aides — and they’re widely underpaid.

2. Which jobs have a future in our economy?

The demographic shifts in the United State’s labor force have happened parallel to, and as a result of, a number of environmental, political, and economic variables, but digital communication and technological advancements have and will make the most impact on our lives and the future of work.

Physical jobs with highly structured and predictable activities on both the production and purchasing ends of capital, including many traditional manufacturing jobs, are quickly being automated, and the McKinsey Global Institute projects over 45% of global work activities could be programmed with currently demonstrated technology.

This makes it easy to weave a scarcity narrative around job growth in the United States alongside apocalyptic images of artificial intelligence taking over the world, but the truth may be less sinister and more complex.

There are plenty of jobs available in the healthcare industry, social services, even in manufacturing — jobs that value collaboration, intuition, and a human touch — along with a gap of skilled workers to take them. And as innovations in robotics make machines safer to work with and cheaper to purchase, a positive collaborative relationship is emerging, mostly led by small- to medium-sized businesses.

Could humans and robots work together towards community well-being?

Green jobs have also been on a steady upward swing, driven by state-level investment in renewable technologies with bipartisan support. In May 2016, U.S. jobs in solar energy overtook those in oil and natural gas, and a Rockefeller Foundation-Deutsche Bank Climate Change Advisors study in 2012 found that energy retrofitting buildings in the United States could create more than 3 million “job years” of employment.

3. How will workforce development programs respond to new working class needs?

If there are indeed enough jobs to go around, and not enough skilled laborers to occupy them, workforce development programs have an increasingly urgent and critical role to play in the future of work.

Unfortunately, many federal workforce programs have been largely redundant and ineffective, according to critics on both sides of the political aisle — and those geared towards seniors, disadvantaged youth, and the disabled are on the chopping block for budget cuts. Challenges for workforce programs across the board have included developing and maintaining strategic partnerships, engaging with employers, and delivering support service strategies tailored to the needs of training participants.

Could an intersectional approach to job training support low-income jobseekers?

Research and strategic investment in workforce programs representing these challenges is already underway — including the 12-month on-the-ground listening and planning process that led to the Quality Jobs Fund. Prior initiatives, like the Human Capital Innovation Fund, are making a strong case for supporting low-income jobseekers in their own communities through sustainable, long-term investment in workforce development, including capacity-building resources in 1) planning, relationship building, and strategy development over time; 2) flexible approaches to implementation that adapt in response to environmental changes; and 3) changing the way program outcomes are measured so they capture the ongoing work of relationship building and employer engagement that is required to design and deliver effective workforce development services.

This intersectional approach to partnerships is also being presented as a strategic solution for making bad jobs better in the current labor market. Workforce practitioners could make allies of community economic developers, labor rights organizations, and values-driven employers within the context of public policies to create new enterprises, new relationships, and new resources.

Sometimes, in order to win, you have to change the rules.

4. How will the new working class advance?

The old jobs aren’t coming back, and neither is the return of the 40-hour workweek, the traditional safety net, or a steady paycheck as we continue on the path of accelerated deindustrialization, leaving workers vulnerable to historic forms of exploitation often disguised as “freedom and flexibility.”

As the demographics of the working class shift, community organizing for quality jobs and equality must broaden to include entire communities: people with jobs, the unemployed, the “anxiously employed,” and people across the social and political spectrum.

The most successful, diverse campaigns of the 21st century have advocated for better pay and working conditions around a simple moral argument that captures the heart of economic inequality and provides intersectional entry points: A full-time job should be enough to cover the basics and support a decent standard of living.

Organizing for community equity must broaden to include entire communities.

Advocates have succeeded in passing living-wage laws across the country for the past two decades, bringing together college students, church members, service workers, day laborers, freelancers, and more through local campaigns. Sometimes these have been led and backed by unions, but new kinds of community groups and coalitions are also forming and mobilizing.

5. What are the social and civic benefits of a post-work future?

Considering the success of mobilizing a diverse group of working class people around raising the wage — could the next frontier of advocacy push for a universal income in anticipation of a post-work future? This utopian vision of the future has had many iterations throughout our intellectual history and raises interesting questions on the benefits of a new working class economy where human time and value is unbound from production and capital. But the flip side of a post-work future isn’t too far from reality: extreme income and wealth inequality, rising poverty, and mass unemployment.

Successful experiments are already being tested in Kenya, where a village is lifting itself out of poverty, with individuals using their basic income to cover basic needs and start small businesses. Though, we have yet to see the effects of a similar model in wealthier countries.

What are the potentials of family, community, and civic engagement in a society where no one is struggling to meet the basic needs of survival?

Joe McGillivray, the chief executive of a small manufacturing business in Minnesota at the frontlines of automation, tells the New York Times, “My big question is: Are we going to be happy? I get a lot of fulfillment from what I do. Will I have that if I work 20 hours a week?” — but the potential of family, community, and civic engagement in a society where no one is struggling to meet the basic needs of survival is tantalizing. What are the new frontiers of possibility for human imagination? Will innovation stagnate or flourish? What is the structural support, education, and organizing needed to encourage individual gratification and community development in this potential new world? What would you do with your time in a post-work future with a basic, universal income?

Find the Quality Jobs Fund on Facebook and Twitter to let us know what you think, and engage in the conversation on the #futureofwork.